After Biden’s election, Democrats assumed that “going big” on new redistributive programs was the key to a progressive future. Research shows why that didn’t work, and pinpoints the path forward: what Democrats and mainstream Republicans need to offer are economic justice initiatives that tap deeply held beliefs that the rich are getting too much, that less privileged workers are paid too little, and that anyone who works hard deserves a stable middle-class life and retirement.

DO’S AND DON’TS FOR BRIDGING THE DIPLOMA DIVIDE

DON’TS

1. Don’t despair. Voters generally want less inequality. When shown pie charts illustrating the distribution of wealth in the US and Sweden (but not identified by country!) 92% of Americans preferred the Swedish distribution of income, where the top quintile holds 36% of wealth (as opposed to 84% in the US)[i] in polling, twice as many people preferred A as B.[ii]

“Construing populist protest as either malevolent or misdirected absolves governing elites of responsibility for creating the conditions that have eroded the dignity of work and left many feeling disrespected and disempowered.” – Michael Sandel

BUILDING CROSS-CLASS SUPPORT FOR ECONOMIC JUSTICE

Reading time: 7 minutes

A.

“To make life better for working people we need to invest in education, create better paying jobs, and make healthcare more affordable for people struggling to make ends meet.”

B.

"To make life better for working people we need to cut taxes, reduce regulations, and get government out of the way of business. "

Not only did 89% of progressives prefer Message A; 63% of persuadables did. Among key demographics (rural/small town voters, self-identified working-class orders, blue-collar voters), the progressive populist candidate garnered more support than all other candidates but…[i]

2. Don’t assume that support for less labor market inequality translates into widespread support for redistribution. Increasing inequality has not led to increased support for programs for the poor.[ii] Black people are supportive, sharply more so than Americans in general.[iii] Middle-status Americans are least supportive of redistributive programs:

Support for making Biden’s childcare tax credit permanent was lowest among middle-income noncollege voters.[iv]

Middle-income voters are most likely to feel that government should provide less or the current level of support for people in need (71%), and least likely to believe government should provide more (28%).[v]

Middle-income Americans oppose universal basic income at rates (59%) closer to high-income (68%) than low-income Americans (35%).[vi]

Why?

People in the middle hierarchies are more motivated by fear of losing what they have than by the prospect of gaining more, more so than either high- or low-status people..[vii]

Americans in the second lowest quintile by household income “virulently distance” themselves from Americans in the lowest quintile as if to say “I work hard, unlike those other people.”[viii]

3. Means-tested programs (but not universal ones) exacerbate middle-class opposition to redistribution. Means-tested programs pit the have-a-little’s against the have-not’s.[ix] JD Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy recounts his resentment when as a grocery store clerk he saw people on welfare with cell phones he couldn’t afford. [x] “The taxes go to the poor, not to us… The middle-income people are carrying the cost of liberal social programs on their backs,” said a blue-collar homemaker.[xi] This sentiment is widespread despite its inaccuracy. Social Security, in sharp contrast, has such widespread support it is the “third rail” of American politics.

4. Means-tested programs trigger racism[xii] and classism. The gap between whites and minorities in support for “welfare” (TANF) began to increase in 2008, driven in part by “racial resentment” aka the belief that African-Americans could get ahead if they just try hard enough without asking for special treatment. Presenting whites with information that most of welfare’s benefits go to white people closes this racial gap.[xiii] (That’s true: most of the people who get TANF are white.) Means-tested programs trigger not only racism but also classism: white rural recipients experience “strong social disgrace around unemployment and welfare receipt” because welfare is associated with laziness and poor moral character.[xiv] Because means-tested programs trigger both racism and classism, they become politically vulnerable and typically yield benefits that are scanty, stigmatized, and sporadic:[xv] childcare subsidies are a good example.[xvi]

5. Don’t assume that the answer is an exclusive focus on class. A well-meaning insistence to abandon “identity politics” will be heard by women and people of color to stop focusing on racism and sexism despite the fact that both groups lag far behind white men in terms of both economic justice and social respect.[xvii] Research shows that all politics is about identity.[xviii]

6. Support the minimum wage but don’t assume that Americans see that as their path to a stable future. Happily, nearly 90% of Democrats, 70% of independents, and over 60% of Republicans support raising the minimum wage, which is crucial: anyone who works full time should be able to support a family.[xix] However, do NOT assume this will respond to the economic anxieties of the fragile and failing middle-class: their goal is a well-paid job that paves the path to a stable middle-class life. Minimum wage jobs are what they are trying to avoid.

DO’S

1. Incessantly drive home the dying of the American dream. Keep reminding voters that until roughly 1980 virtually all Americans did better than their parents, but only about half of those born in the 1980s will.[xx] Today, the US ranks towards the bottom of industrialized countries in terms of social mobility.[xxi] Providing information about income and earnings inequality increases Americans’ belief that lower status groups (low-income, Black and Latinx) face structural disadvantage.[xxii]

2. Stress policies that tap into Americans’ belief they can no longer get ahead by working hard. Policies that address labor market inequality are more popular than redistribution.[xxiii] Americans’ belief they can get ahead by working hard plummeted from 76% to 53% between 2001-2012, and currently stands at 60%.[xxiv] Latinx are particularly strong believers in hard work:[xxv] Low-income Republicans are 19% more likely than high-income Republicans to agree that hard work and determination are no guarantee of success.[xxvi] Donald Trump was initially successful at increasing optimism about upward mobility among both whites and Latinx Americans, although Black Americans’ optimism dropped after his election.[xxvii] Importantly, Americans’ optimism has plummeted from 65% to 47% since 2018.[xxviii] The widespread sense that the labor market is rigged is driven by pessimism about one’s own prospects for economic mobility.

3. Stress policies that tap into Americans’ belief that the rich are paid too much and others are paid too little. Even before Occupy Wall Street, half to two-thirds of Americans believed that income differences were too large, and rejected the explanation that this was necessary for prosperity. Polling consistently finds that 70% to 86% of Americans believe that the rich are paid too much, a view shared across racial groups.[xxix] They also believe that skilled and unskilled workers are paid too little.[xxx] Americans know that getting ahead is often linked to “knowing the right people” and think this is unfair: that belief drives opposition to income inequality.[xxxi] Populist messages that explicitly call out elites are popular, particularly among working-class voters.[xxxii]

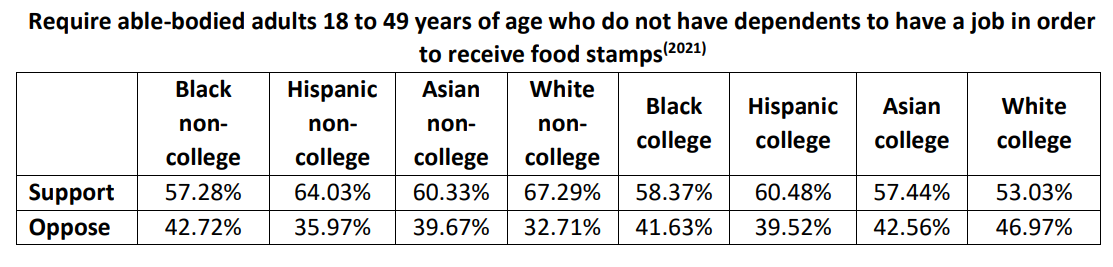

4. Tap Americans’ endorsement of universal programs where benefits are seen as rewards for hard work. Astonishingly, between half and two-thirds of every racial group supports work requirements on food stamps (yikes).[xxxiii] This definitely reflects racism when applied to African-Americans – but racism is not the only thing in the mix.[xxxiv]

Across racial groups, a core working-class value is hard work/responsibility: “If I won the lottery I would still work, because that’s how I get my self-esteem.”[37] This explains why half to three-quarters of Americans support greater spending on Social Security and Medicare benefits, which are perceived as rewards for hard work, as are disability benefits and the earned income tax credit.[38] Middle-income people most strongly agree that Social Security won’t be there for them when they retire, a trend that could corrode support for Social Security: strong messaging that all Social Security needs is some actuarial tweaks is vital and long overdue.[39] Strong support (57%-77%) across racial and income groups exists for lowering the eligibility age for Medicare to 50, although messaging is important: swing working-class voters prefer to promise “increased access to affordable healthcare” rather than “Medicare for all.”[40]

5. Message the carework infrastructure as empowering Americans to get to work and stay employed. This works for many programs that are sorely needed, notably universal Pre-K and paid leave.

6. Address the geographic maldistribution of economic opportunity. The US has two economies: a blue-state economy where GDP increased by 36% and a red-state economy that saw 2% decline in the decade before 2018.[41] Bill Clinton campaigned on an industrial policy to revive manufacturing in the Rust Belt but then implemented neo-liberal policies that undercut unions, exacerbated deindustrialization, and led to widespread foreclosures.[42] Rural areas saw similar levels of disinvestment. Rural Organizing found that 94% of respondents agreed that, “The rural and small-town way of life is worth fighting for” – to some, it seems only the far right have been fighting for it.[43] This geographic maldistribution of economic opportunity is not only unfair; it’s suicidal in a country that gives rural and Rust Belt voters disproportionate political power in the Electoral College and in the Senate.

7. Connect the economic struggles of people in high-cost areas to the struggles of people in areas left behind. Only the winners win in winner-take-all cities; less-privileged people often cannot afford high rents or to access the homeownership that has been the traditional path to intergenerational wealth. (I speak as a resident of San Francisco.)

8. Tap Americans’ negative feelings towards corporate power run amok by sharply differentiating between big and small business. Today 74% of Americans are somewhat or very dissatisfied with the size and influence of major corporations, whereas over 70% of Americans have a high level of trust in small business.[44] Working-class voters strongly support candidates who own small businesses: The aspiration to own a small business is a widespread blue-collar ideal — it’s the fantasy of an order-taker to be an order-giver.[45] Distinguish between rapacious power of corporate power run amok and the mom-and-pops many noncollege grads aspire to run—and that powerful companies like Amazon and Uber often bleed dry.

10. Don’t reinforce the far right’s “makers and takers” narrative. After the Great Recession, Fox News redirected anger away from business elites through a narrative contrasting “makers and takers,” intimating that blue-collar workers, small business owners, and Big Business occupy the same social role as “makers.” To quote Roger Ailes, “Every time I needed a job, I had to go to the rich guy. I love the poor guy. He had no job…I’m not going to let anyone divide me against the people who actually gave me the jobs.”[46] Distinguishing between mom-and-pops and corporate giants undercuts this argument.

Sample messages:

(from Commonsense Solidarity)[47]

This country belongs to all of us, not just the superrich. But for years, politicians in Washington have turned their backs on people who work for a living. We need tough leaders who won’t give in to the millionaires and the lobbyists, but will fight for good jobs, good wages, and guaranteed healthcare for every single American.”

(My suggestion) We need a pro-small business, pro-worker government that brings people together to recapture the American dream and create a country where hard work pays off in stable middle-class life. The fat cats are trying to set us against each other, but if we work together we can make the investments that allow people to get to work: from bridges and roads to affordable child- and healthcare. Rebuilding the American middle class means restoring access to homeownership and good jobs from coast to coast, no matter where you live, and empowering small business while reining in the power and pay of CEOs who drive mom-and-pops out of business.

11. Express support for unions, which made the American middle class. Support for unions has climbed sharply in recent years: in 1977, only 33% of nonunion, nonsupervisory workers said they would vote for a union but by 2021, 69% expressed support for unions.[48] Unions provide their members with greater access to benefits, and an important wage boost, particularly for people of color but also for white people.[49] Unions also build class consciousness.

Many thanks to Hazel Marcus for her review of this white paper.

[1] Norton, M. I., & Ariely, D. (2011). Building a Better America—One Wealth Quintile at a Time. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 9–12.

[2] Haney-López, I. (2019). Merge left: Fusing race and class, winning elections, and Saving America, 244. essay, The New Press.

[3] Jacobin Editors. (2021, September 11). Commonsense solidarity: How a working-class coalition can be built, and maintained, 12. Jacobin. Retrieved May 26, 2022, from https://jacobinmag.com/2021/11/common-sense-solidarity-working-class-voting-report; McCall, L. (2013). The Undeserving Rich: American Beliefs about Inequality, Opportunity, and Redistribution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139225687

[4] McCall, L. (2013). The Undeserving Rich: American Beliefs about Inequality, Opportunity, and Redistribution, 191-201. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139225687

[5] Lindh, A., & McCall, L. (2022, April 23). Bringing the market in: an expanded framework for understanding popular responses to economic equality. Socio-Economic Review, 00(0), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwac018

[6] American Compass (2021, September 14). Americans support a generous child benefit tied to work. American Compass. Retrieved June 15, 2022, from https://americancompass.org/essays/child-tax-credit-expansion-survey/

[7] Pew Research Center. (2020, May 27). Views of the Economic System and Social Safety Net. Pew Research Center. Retrieved June 15, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/12/17/views-of-the-economic-system-and-social-safety-net/

[8] Gilberstadt, H. (2021, January 6). More Americans oppose than favor the government providing a universal basic income for all adult citizens. Pew Research Center. Retrieved June 16, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/19/more-americans-oppose-than-favor-the-government-providing-a-universal-basic-income-for-all-adult-citizens/

[9] Duguid, M. M., & Goncalo, J. A. (2015). Squeezed in the middle: The middle status trade creativity for focus. Journal of personality and social psychology, 109(4), 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039569

[10] Halpern-Meekin, S., Sykes, J., Tach, L., Edin, K. (2015). It's Not Like I'm Poor: How Working Families Make Ends Meet in a Post-Welfare World. United States: University of California Press.

[11] Rieder, J. (2009). Canarsie the Jews and Italians of Brooklyn against Liberalism. Harvard University Press.

[12] Vance, J. D. (2018). Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis, 139. United Kingdom: HarperCollins.

[13] Rieder, J. (2009). Canarsie the Jews and Italians of Brooklyn against Liberalism. Harvard University Press.

[14] Gilens, M. (2009). Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media, and the Politics of Antipoverty Policy. University of Chicago Press; Hancock, A. (2004). The Politics of Disgust: The Public Identity of the Welfare Queen. NYU Press; Neubeck, K. J., and Cazenave, N. A. (2002). Welfare Racism: Playing the Race Card against America’s Poor. Routledge.

[15] Wetts, R., and Robb, W. (2018). Privilege on the Precipice: Perceived Racial Status Threats Lead White Americans to Oppose Welfare Programs. Social Forces 97(2), 793– 822.OLIVER

[16] Sherman, J. (2009). Those Who Work, Those Who Don't: Poverty, Morality, and Family in Rural America, 57. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; Brown-Iannuzzi, J.L., Lundberg, K.B., & McKee, S.E. (2017). Political Action in the Age of High‐Economic Inequality: A Multilevel Approach. Social Issues and Policy Review, 11, 232-273; Bobo, L., & Hutchings, V. L. (1996). Perceptions of racial group competition: Extending Blumer's theory of group position to a multiracial social context. American Sociological Review, 61(6), 951–972. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096302; Wetts, R., & Willer, R. (2019). Who Is Called by the Dog Whistle? Experimental Evidence That Racial Resentment and Political Ideology Condition Responses to Racially Encoded Messages. Socius. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023119866268

[17] Sherman, J. (2009). Those Who Work, Those Who Don't: Poverty, Morality, and Family in Rural America. (p. 123). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

[18] Williams, J. C., & Boushey, H. (2017, April 27). The three faces of work-family conflict. Center for American Progress. Retrieved May 26, 2022, from https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-three-faces-of-work-family-conflict/

[19] Lilla, M. (2017). The Once and Future Liberal: After Identity Politics. United States: HarperCollins.

[20] Achen, C. H., Bartels, L. M. (2017). Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government. Germany: Princeton University Press.

[21] America's hidden common ground on economic opportunity and inequality. Public Agenda. (2020, September 24). Retrieved June 28, 2022, from https://www.publicagenda.org/reports/americas-hidden-common-ground-on-economic-opportunity-and-inequality/

[22] Chetty, R., Grusky, D., Hell, M., Hendren, N., Manduca, R., & Narang, J. (2017, April 24). The fading American Dream: Trends in absolute income mobility since 1940. Science (New York, N.Y.). Retrieved July 5, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28438988/

[23] World Economic Forum. (2020, January). Global Social Mobility Report - World Economic Forum. Retrieved July 5, 2022, from https://www3.weforum.org/docs/Global_Social_Mobility_Report.pdf

[24] Dietze, P., McCall, L., Craig, M. A., & Richeson J.A. (2022). Rising income inequality and the multidimensional perception of (un)-equal economic opportunity. Under review.

[25] Lindh, A. & McCall, L. (2021 September 11). Reconsidering the Popular Politics of Economic Inequality in the United States. Unpublished.

[26] McCall, L. (2013). The Undeserving Rich: American Beliefs about Inequality, Opportunity, and Redistribution, 182. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139225687; Leslie’s PowerPoint, 15.

[27] Lopez, M. H., Gonzalez-Barrera, A., & Krogstad, J. M. (2020, July 27). Latinos are more likely to believe in the american dream, but most say it is hard to achieve. Pew Research Center. Retrieved June 8, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/09/11/latinos-are-more-likely-to-believe-in-the-american-dream-but-most-say-it-is-hard-to-achieve/; McCall, L. (2016). “Political and Policy Responses to Problems of Inequality and Opportunity: Past, Present, and Future” in The Dynamics of Opportunity in America: Evidence and Perspectives. Germany: Springer International Publishing; Leslie’s Powerpoint, 13.

[28] McCall, L. (2013). The Undeserving Rich: American Beliefs about Inequality, Opportunity, and Redistribution, 112. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139225687

[29] McCall, L. (2016). Political and policy responses to problems of inequality and opportunity: Past, present, and future. The Dynamics of Opportunity in America, 415–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25991-8_12

[30] McCall, L. (2016). Political and policy responses to problems of inequality and opportunity: Past, present, and future. The Dynamics of Opportunity in America, 415–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25991-8_12

[31] McCall, L. (2013). The Undeserving Rich: American Beliefs about Inequality, Opportunity, and Redistribution, 210-212. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139225687; Leslie’s PowerPoint, 10.

[32] McCall, L. (2013). The Undeserving Rich: American Beliefs about Inequality, Opportunity, and Redistribution, 157-168. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139225687

[33] McCall, L. (2013). The Undeserving Rich: American Beliefs about Inequality, Opportunity, and Redistribution, 156. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139225687

[34] Jacobin Editors. (2021, September 11). Commonsense solidarity: How a working-class coalition can be built, and maintained, 5. Jacobin. Retrieved May 26, 2022, from https://jacobinmag.com/2021/11/common-sense-solidarity-working-class-voting-report

[35] Astrow, A. (2021, May 2). The college degree conundrum: Democrats' path forward with non-college voters . Third Way. Retrieved June 21, 2022, from https://www.thirdway.org/memo/the-college-degree-conundrum-democrats-path-forward-with-non-college-voters (Custom breakdowns generated for Third Way)

[36] Winter, N. J. (2006). Beyond welfare: Framing and the racialization of White Opinion on Social Security. American Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 400–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00191.x;

[37] Lamont M. (2002). The dignity of working men: Morality and the boundaries of race, class, and immigration. Russell Sage Foundation.

[38] Sherman, J. (2009). Those Who Work, Those Who Don't: Poverty, Morality, and Family in Rural America, 147. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; The Century Foundation. (2021, May). Voters Overwhelmingly Support Strengthening Supplemental Security Income (SSI). Data For Progress. Retrieved June 8, 2022, from https://www.filesforprogress.org/memos/dfp_tcf_ssi_may_2021.pdf; Sykes, J., Križ, K., Edin, K., & Halpern-Meekin, S. (2015). Dignity and Dreams: What the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) Means to Low-Income Families. American Sociological Review, 80(2), 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122414551552

[39] Collinson, C., Rowey, P., & Cho, H. (2021, November). A compendium of findings about the retirement outlook of U.S. workers. Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies. Retrieved May 27, 2022, from https://transamericainstitute.org/docs/default-source/research/2021-retirement-outlook-compendium-report.pdf

[40] Astrow, A. (2022, February 20). How does education level impact attitudes among voters of color? . Third Way. Retrieved May 27, 2022, from https://www.thirdway.org/memo/how-does-education-level-impact-attitudes-among-voters-of-color; Jacobin Editors. (2021, September 11). Commonsense solidarity: How a working-class coalition can be built, and maintained, 5, 44. Jacobin. Retrieved May 26, 2022, from https://jacobinmag.com/2021/11/common-sense-solidarity-working-class-voting-report

[41] Moretti, E., Moretti, E. (2012). The New Geography of Jobs. United States: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; Edsall, T. (2019, September 25). Red and blue voters live in different economies. The New York Times. Retrieved May 26, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/25/opinion/trump-economy.html

[42] McQuarrie, M. (2017). The revolt of the Rust Belt: place and politics in the age of anger. The British Journal of Sociology, 68(S1), 120–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12328

[43] Haney-López, I. (2019). Merge left: Fusing race and class, winning elections, and Saving America, 175. The New Press.

[44] Slade, S. (2022, May 1). The Party of big business is getting more anti-conservative by the day. The New York Times. Retrieved May 27, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/01/opinion/desantis-republicans-disney.html; Brenan, M. (2021, November 20). Americans' confidence in major U.S. institutions dips. Gallup. Retrieved May 27, 2022, from https://news.gallup.com/poll/352316/americans-confidence-major-institutions-dips.aspx

[45] Jacobin Editors. (2021, September 11). Commonsense solidarity: How a working-class coalition can be built, and maintained, 24. Jacobin. Retrieved May 26, 2022, from https://jacobinmag.com/2021/11/common-sense-solidarity-working-class-voting-report

[46] Peck, R. (2019). How Fox News Hosts Imagine Themselves and Their Audience as Working Class. In Fox Populism: Branding Conservatism as Working Class. Communication, Society and Politics, 165. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108634410.005

[47] Jacobin Editors. (2021, September 11). Commonsense solidarity: How a working-class coalition can be built, and maintained, 21. Jacobin. Retrieved May 26, 2022, from https://jacobinmag.com/2021/11/common-sense-solidarity-working-class-voting-report

[48] Kochan, T. A., Yang, D., Kimball, W. T., & Kelly, E. L. (2018). Worker Voice in America: Is there a gap between what workers expect and what they experience? ILR Review, 72(1), 3–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793918806250

[49] Frymer, P., Grumbach, J., & Ogorzalek, T. (2022). Unions Can Help White Workers Become More Racially Tolerant. In A. Cornell & M. Barenberg (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Labor and Democracy (Cambridge Law Handbooks, pp. 180-198). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108885362.015